The Writing Life of: Paul Tudor Owen

Paul Tudor Owen

This week I am thrilled to be interviewing author Paul Tudor Owen. Paul Tudor Owen will be sharing with us details of his writing life, telling us all about his latest book ‘The Weighing of the Heart‘, which was released on 22nd March 2019 and answering a few fun questions too. This post contains affiliate links.

Paul Tudor Owen was born in Manchester in 1978, and was educated at the University of Sheffield, the University of Pittsburgh, and the London School of Economics.

Paul Tudor Owen began his career as a local newspaper reporter in north-west London, and currently works at the Guardian, where he spent three years as deputy head of US news at the paper’s New York office.

His debut novel, The Weighing of the Heart, won the People’s Book Prize 2020 and was longlisted for Not the Booker Prize 2019.

1) As a child did you have a dream job in mind?

I always wanted to write novels, but I remember just before leaving university being very conscious that it would be an incredibly difficult way to make a living. So I decided to try to go into journalism, thinking that a lot of the things I would enjoy about writing I would find in journalism too. I started off as a local reporter in north-west London and eventually got a job at the Guardian, where I work today.

The two forms of writing are similar in some ways, but they can also be very different. I’ve mostly been in news journalism rather than feature writing, so your main priority is to communicate as quickly as clearly to the reader as possible, whereas when you’re trying to write fiction, I think you’re trying to do many things simultaneously – establishing characters, making sure the mechanics of the plot work, working the themes in, writing convincing dialogue, and then I hope also trying to do something interesting with the structure, trying to subvert the reader’s expectations, trying to do something the reader hasn’t seen before, or at least not in that form.

You might actually not want something to be clear as quickly as possible – you might want the opposite, you might want to hold that idea or that fact back.

I’m sure that in feature writing and some forms of long-form journalism or creative non-fiction, people are juggling some of these ideas. But not really in the news.

2) Who was your favourite childhood author (s)?

I’ve realised recently that my novel The Weighing of the Heart was very much influenced by a lot of the books I studied during my A-level English literature course.

It’s about a young British guy living in New York called Nick Braeburn, who moves in with a couple of rich older ladies as a lodger in their opulent apartment on the Upper East Side in Manhattan. He gets together with their other tenant, Lydia, who lives next door, and the two of them steal a priceless work of art from the study wall.

The work of art that Nick and Lydia take is an Ancient Egyptian scene, and as the stress of the theft starts to work on them, the imagery of Ancient Egypt, the imagery in the painting, starts to come to life around them, and it’s intended to be unclear whether this is something that is really happening or whether it’s all in Nick’s head.

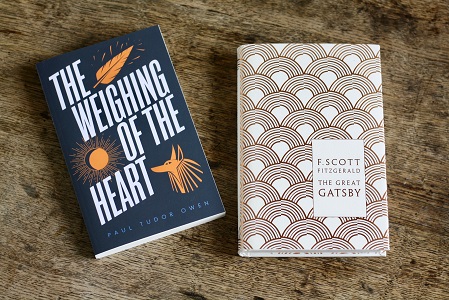

At A-level I had a great teacher and we studied some fantastic books, including The Great Gatsby, The Remains of the Day, The Catcher in the Rye… All of those had a big impact on me in different ways and you can see their influence in The Weighing of the Heart: The Catcher in the Rye for its depiction of New York, The Great Gatsby for its elegiac tone and study of the American Dream, and The Remains of the Day for its peerless use of the unreliable narrator.

The Weighing of the Heart and one of its influences, The Great Gatsby

And then at university I loved the modernists like Faulkner, Eliot, Woolf, the idea of fractured narratives, and I took a great course on contemporary writers that introduced me to postmodernism – John Fowles, Salman Rushdie, Julian Barnes – and the idea that you could present the reader a story within a story and play with their perception of exactly what they were reading. I didn’t go down this exact route with The Weighing of the Heart in the end, but it’s something I want to explore with my next book.

3) What is your average writing day like? Do you have any special routines, word count, etc?

I wrote a lot of The Weighing of the Heart at my kitchen table and on my sofa in my old flat in north London. Then I got a job in the Guardian’s New York office and we lived there for the next few years, and I finished the ending of the book in a library quite near our flat, in SoHo, just round the corner from where David Bowie lived. We only had a very small flat so it would have been pretty antisocial to write at home.

Then later my office moved to a co-working space run by WeWork, which meant that at the weekends I could book space in any of the other WeWork offices anywhere in New York.

So when I would work on my writing on Saturdays or Sundays I would go to a different WeWork office each time, which was great because I really got to explore the city and work in lots of different places, and it was great to feel immersed in New York and to be seeing the sights of the city out of the window as I was working. There was one in Midtown that I really liked with a great view into the forest of skyscrapers. I came downstairs from one in Tribeca once at about 5pm and the other WeWorkers were having a rave on the ground floor.

Now I’m back in London and we’ve just had a baby, so when and where and how I write is very much a work in progress… Before our baby was born though I would work in the kitchen with as much natural light as possible. I would get a cup of tea and a nice glass of squash… I’ve never been the Charles Bukowski type of writer who would be downing shots of whiskey and furiously tapping out whatever drunken visions came to me.

4) How many books have you written? Any unpublished work?

I wrote two unpublished books before The Weighing of the Heart – but I’m not sure now that either of them was really ready for primetime.

5) Are you a plotter or a pantser?

I usually start with the spark of an idea for a scene: some dialogue, or something about the relationship between two characters. Then from there I’ll start writing until I reach a point where I feel like I have to plot out the ending, which I always find by far the most difficult bit. The Weighing of the Heart probably went through four or five endings until I felt I had got it right. And with the book I’m working on now I’m finding the ending a nightmare too.

Concerning your latest book:

Publisher – Obliterati Press

Pages – 254

Release Date – 22nd March 2019

ISBN 13 – 978-1999752842

Format – ebook, paperback

‘Sooner or later, everybody comes to New York…’

Following a sudden break-up, Englishman in New York Nick Braeburn takes a room with the elderly Peacock sisters in their lavish Upper East Side apartment, and finds himself increasingly drawn to the priceless piece of Egyptian art on their study wall – and to Lydia, the beautiful Portuguese artist who lives across the roof garden.

But as Nick draws Lydia into a crime he hopes will bring them together, they both begin to unravel, and each finds that the other is not quite who they seem.

Paul Tudor Owen’s intriguing debut novel brilliantly evokes the New York of Paul Auster and Joseph O’Neill, and has been nominated for the Summer 2019 People’s Book Prize for fiction.

Amazon.co.uk – Amazon.com – Amazon.in – Blackwells

6) How did you go about researching the content for your book?

The first aspect of The Weighing of the Heart you could say I researched was New York. I’d had an obsession with New York since I was a teenager. It felt like all these great novels and films and songs I loved were set in New York – The Great Gatsby, Mean Streets, Simon and Garfunkel. It felt like a place where anything could happen, it felt like a great crucible of art and culture where anyone who was anyone either came from or had made their name or had depicted it so memorably.

And that led me to study American literature and American history at university, and the third year was a year abroad, and I went to the University of Pittsburgh, and that was when I was able to visit New York for the first time myself.

And walking those streets, all the unmistakable iconography of New York around you – the fire escapes, the yellow cabs, steam rising from a manhole, the skyscrapers, the rivers – it just felt like I’d walked into one of those books or films that I’d loved.

And I not only wanted to live there, I wanted to be part of this great tradition of depicting New York and romanticising it.

And when we did move there, I’d already written quite a lot of The Weighing of the Heart, so in some ways it really did feel like life imitating art.

I used to enjoy walking the same streets that Nick and the other characters in the book would walk, visiting the galleries and restaurants and streets that they visit in the book. There’s a real apartment block on the Upper East Side, just across from Central Park, that I used as the model for the Peacock sisters’ apartment block.

Paul Tudor Owen outside the building that was the model for the Peacocks’ home

I’d wanted to live there for so long that I did sometimes wonder if this was really happening. I remember when I was a kid watching an episode of Red Dwarf, the sci-fi TV sitcom from the 90s, where the lead character, Lister, gets hooked on this immersive virtual-reality computer game called Better Than Life. And in the game he thinks he is living in Bedford Falls, the town from It’s a Wonderful Life, and he loves it and he doesn’t want to leave. And sometimes after moving to the US I got a bit worried that I was in Better Than Life, that I would wake up and I’d be still a teenager in Manchester reading The Catcher in the Rye, fantasising about New York.

The second area I had to research came from an exhibition I went to a few years ago at the British Museum called The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, which told the story of what the Ancient Egyptians believed happened to you when you die.

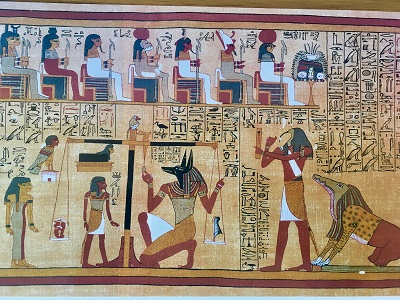

As I learnt from the exhibition, the Ancient Egyptians believed in a ceremony called ‘the weighing of the heart’, something in some ways similar to the Christian idea of St Peter standing at the gates of Heaven, deciding whether or not you have lived a worthy enough life to come in.

In the Ancient Egyptian version, Anubis, the god of embalming, presides over a set of weighing scales, with the heart of the dead person on one side and a feather on the other.

If the heart is in balance with the feather, you get to go to the afterlife, which they called the Field of Reeds. But if your heart is heavier than the feather, you get eaten by an appalling monster called the Devourer, who has the head of a crocodile, the body of a lion, and the back legs of a hippopotamus – three of the most dangerous creatures that Ancient Egyptians could encounter.

To the Ancient Egyptians, the heart, rather than the brain, was the home of a person’s mind and conscience and memory, which was why it was the heart they were weighing.

And, intriguingly, one thing they were afraid of was that the heart would actually try to grass you up during this ceremony – sometimes the heart would speak up and reveal your worst sins to Anubis at this crucial moment. You could prevent this from happening by keeping hold of a little ‘heart scarab’.

The Ancient Egyptian weighing of the heart ceremony

I was spellbound by this ornate mythology, which had formed over centuries and millennia; I loved the way it was so familiar in its overall concept but so strange and unfamiliar in its details.

And I realised that the painting Nick and Lydia should steal should be an image of this ceremony, the weighing of the heart. It was so fitting, because the book is essentially about guilt and innocence; it’s about you weighing up as a reader how much you trust Nick as a narrator, and it’s about Nick himself and the people around him weighing up how much they trust him, what they think of him, what they know about him and his character. And without spoiling it for anyone who hasn’t read it, I hope that I found a way to knit all that imagery into the book effectively, especially towards the end.

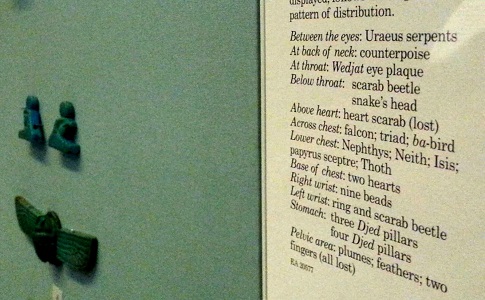

Once I’d settled on this, there were a number of strange coincidences. At one point in The Weighing of the Heart Nick recalls a school trip to the British Museum, and it is suggested he might have stolen one of these heart scarabs that could protect you during the ceremony. I had written this scene but I wanted to get the details right, so I looked through the British Museum’s collection of scarabs on their website and identified the one that best fit the bill, and then I went down to the museum to take a look at it in person.

But when I got there and found the case where this scarab was supposed to be, the space for this scarab was empty. Instead of the object itself there was just a note on the wall that said: ‘Heart scarab (lost).’

‘Heart scarab (lost)’ – missing scarab at the British Museum

It was another strange moment of life imitating art.

7) How long did it take to go from ideas stage to writing the last word?

I think I started the book around 2011, and once I’d written the first couple of chapters I quickly felt quite confident that what I was writing was much better than anything that I’d written before.

I had found an agent after working on a previous book that never found a publisher. So I went to him with the beginning of The Weighing of the Heart, but because of the failure of the first book, he seemed to have more or less lost interest.

So I was faced with a choice. You’re usually told as an author – especially when you’re starting out – that you will never get anywhere without an agent, and that if you have managed to get one you should do everything you can to keep them.

I’m sure there is a lot of truth in that. But I felt that if I stayed with this agent, that was not going to result in this book getting published.

So I amicably cut ties with him and set about trying to find someone new. And luckily that turned out to be a much easier process than it had been in my early 20s. In those days agents had all expected manuscripts to be delivered by post, and I remember every weekend printing out page after page of my chapters, stapling these bundles together, taking them to the post office… It was very time-consuming.

But by the time I came to find a new agent, the world of agents had finally discovered email, and that vastly simplified the whole system. I finished work one day and went to a secluded spot in the office, and started working my way from A to Z through The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, which lists all the agents in the UK, sending out my first two chapters to as many agents as I could. I think that first night I got about half way through the alphabet, to about M, and by the next morning, or the morning after that, I was already getting some interest, which was really heartening.

And I eventually started working with a brilliant agent, and I finished a workable draft of The Weighing of the Heart and we started sending it out.

But at that point I had a stroke of bad luck. Another book about art theft in New York – The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt – had just come out, and it was a massive hit. It was everywhere. Again and again I heard from publishers: “We really like your book, but it’s just too similar to The Goldfinch.”

Tartt’s debut novel, The Secret History, was a big influence on me, especially in its tone and pace, and I actually remember reading the news that she had a new book out on my phone on the way to work one day – a book set in New York, all about the theft of a painting. I distinctly remember thinking: “Oh no, that sounds very similar to my idea. I hope that doesn’t make things difficult for me.”

And then I moved to New York and started a new job and life became extremely busy and complicated, and I don’t do any work on my novel or on trying to get it published for the next year or so.

When things started to settle down a bit, I went back to my agent, but she said she didn’t feel that she could send it out to anyone else because a number of publishers had turned it down already.

So again I was faced with a choice. I could just leave the manuscript in my metaphorical desk drawer and get on with something else. But I knew that it was a good book and it felt frustrating that it was sitting there, unread.

So I decided to send it out to small publishers myself. And again I went through the Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook and the US equivalent, Writers’ Market, starting at A and sending out the first two chapters to as many publishers as I could.

And the response was very positive. The received wisdom in the literary world is that publishers will only talk to you if you’ve gone through an agent, and that may well be true for the big publishing houses. But many smaller presses seemed happy to consider my book without an agent being involved.

I had a really productive discussion with Obliterati Press, a small publishing house in the UK set up by two writers whose whole purpose is to get books out there that they feel enthusiastic about, which otherwise might not see the light of day. They agreed to publish it, and it was a great process working with them.

Signing my publication deal ended up roughly coinciding with our return to London from New York – and it felt very exciting to be coming back to the UK ready to achieve this ambition that I had been working towards for so long.

8) How did you come up with the title of your book?

The book was actually called The Locked Study for a long time – the Peacock sisters’ study is where the painting is that Nick and Lydia steal. But perhaps that made it sound too much like a Sherlock Holmes novel. As soon as I changed the title to The Weighing of the Heart – the name of the Ancient Egyptian scene depicted in the painting – publishers were suddenly much more interested.

9) Can you give us an insight into your characters?

Nick, the narrator, is the key character and once I’d decided I wanted to write the novel in the first person, getting his voice right was crucial.

I was always interested in establishing an unreliable narrator for this book who you initially trust and like, and then gradually become suspicious of – an interest that goes back to books like The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro, a stunning novel about the prospect of wasting your life and the lengths you can go to hide that from yourself. By the end of that book what the narrator, Stevens, is saying and what you as the reader take from that are two completely different things. It’s so skilfully done.

Another book I was thinking of when I was creating Nick’s voice was My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier, which is about a man who suspects the woman he loves is poisoning him. Throughout the novel, Du Maurier demonstrates an incredible ability to keep two entirely contradictory interpretations of the plot completely plausible in your mind, and I was aiming for something along those lines too.

And then from an early stage of drafting it I wanted Nick to be a Brit in New York, an outsider. Partly this was to allow myself to live out my fantasy of living in New York. But partly it was because New York is a city of immigrants and newcomers and a melting pot for artists from around the globe and around America just as it is for everyone else, and I felt that that idea would come across most effectively through a foreigner.

In my view, some of the best writing and art and music about New York often comes from outsiders to the city who are looking at the place with fresh eyes. PJ Harvey, for example – whose Stories from City, Stories from the Sea is a quintessential New York album – is from Dorset, and I’ve always loved her description of a conversation on “a rooftop in Brooklyn / At one in the morning … We lean against railings / Describing the colours / And the smells of our homelands / Acting like lovers.”

Perhaps most significantly for my book, which is strongly indebted to The Great Gatsby, F Scott Fitzgerald was from the Midwest, and his narrator in that unsurpassable depiction of New York, Nick Carraway, takes care to point out that all its key characters, “Tom and Gatsby, Daisy and Jordan and I, were all Westerners, and perhaps we possessed some deficiency in common which made us subtly unadaptable to Eastern life.”

I wanted my narrator, Nick Braeburn, to share some of these qualities, and gave him a similar name for that reason.

10) What’s next for you writing wise?

I’m currently working on a new novel, which is essentially about this current phenomenon of lack of trust in the media, in authority, fake news, conspiracy theories.

It’s set in New York again but it’s going to be set in the 1970s when New York was a sort of crime-plagued hellhole. That was the kind of New York that I first fell in love with as a kid through films like Taxi Driver and Mean Streets.

To me that was a time when New York felt so exciting but also so gritty and I really wanted to sort of conjure up New York in my writing. It’s about a failing newspaper journalist who starts looking into conspiracy theories about the moon landings and he starts meeting these conspiracy theorists who believe the moon landings were faked. And as he gets drawn deeper into the world he sort of finds himself against his better judgment starting to believe some of their paranoia.

Unfortunately I’ve just missed the 50th anniversary of the moon landings, but hopefully I’ll have it finished in time for the 60th.

Fun Questions

1) If you could have any super power for the day which would you choose?

It would be hard to turn down the ability to fly, but that Jedi mind trick where you can persuade anyone to do anything would be very useful when it comes to selling my next book.

2) Do you have any pets?

I try not to admit this to anyone because it instantly makes me so unlikeable, but I’ve never really been a fan of pets. I do like human beings though.

3) If you decided to write an autobiography of your life, what would you call it?

The Big Ap-Paul: One Man’s Journey from Manchester to Manhattan

4) Your book has been made into a feature film and you’ve been offered a cameo role, which part would you choose, or what would you be doing?

It would be a lot of fun to play Martin Samarkos, Nick’s artistic rival; Samuel Latza, who owns the gallery where Nick works; or Marty Gamble, the obnoxious actor who lives next door and pervs over Lydia all the time.

I do think The Weighing of the Heart is very cinematic and would make a great film or TV show. It would be fantastic to see some young British superstar like Robert Pattinson play Nick, and Lydia would be a great role for a talented actress on the rise such as Ana de Armas, Julia Fox or Jodie Comer. I’d love to see it on the screen.

5) Where is your favourite holiday destination?

For so long before I got to move there I would visit New York as often as I could, but it’s not exactly a holiday destination for me any more, more a home away from home.

I’ve always loved Venice – I remember the first time I visited thinking it was like a city from another dimension, where cities were based around rivers instead of roads. I love the way so much ordinary business is transacted using the water: boats collecting the rubbish and the recycling, post office boats, the lot. And the silence at night is so strange and eerie for such a bustling city.

It’s also a very satisfying place to visit for an enthusiastic amateur photographer. As a friend of mine said recently: in Venice, only a bad person can take a bad picture.

6) A baseball cap wearing, talking duck casually wanders into your room, what is the first thing he says to you?

‘Excuse me… Is this the way to the New Yorker cartoon caption contest?’

I would like to say a big thank you to Paul Tudor Owen for sharing with us details of his writing life and for a wonderful interview.

I love the cover of his book. It was cool to read where he got some inspiration from.

What an unusual and interesting dichotomie

I do love the sound of this book. I would love to know your views if you decide to read it. Great interview.

Thanks for commenting. Glad you like the look of Paul’s book and the interview.

I completely agree.

Glad you like the interview.